malaysian naturalist, dec 2019

MNS Selangor’s specific legal experience was its battle to stop the East Klang Valley Expressway (EKVE) from cutting through the Gombak Selangor quartz ridge, which is unique, biodiverse and delicate.

MNS sued the government and won a six-month stop work order, but the win was short lived, Pasupathy told the Tapir Talks Public Forum Series, which held its second session in October. “We found that the company was countersuing us, and they said if you want to discuss (the matter), please put RM52.4 million on the table.” She said this put a full stop in the proceedings due to lack of funds and lack of support by residents of affected areas.

Conservation, however, is a game of losses and wins, as the audience heard during Tapir Talks 2.0 with its theme, “80 Years of MNS: Trials and Triumphs”, focusing on MNS Branches of Selangor, Johor, Kedah and Kuching, Sarawak.

For Selangor, other losses included the closure of the Sepang Environmental Interpretive Centre to make way for road development, as well as forest clearing for housing development in Bukit Bayu and Bukit Lagong.

The wins, though, do happen. The main item, Pasupathy said, was Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad remarking on the uniqueness of the Gombak Selangor quartz ridge and a push to make it a heritage site, which would hopefully protect its biodiversity. Others included the active nature of the Branch’s nine Special Interest Groups; collaborations with other NGOs and Councils, such as Majlis Bandaraya Petaling Jaya; publication of a bird book; and participation in MNS events and scientific expeditions.

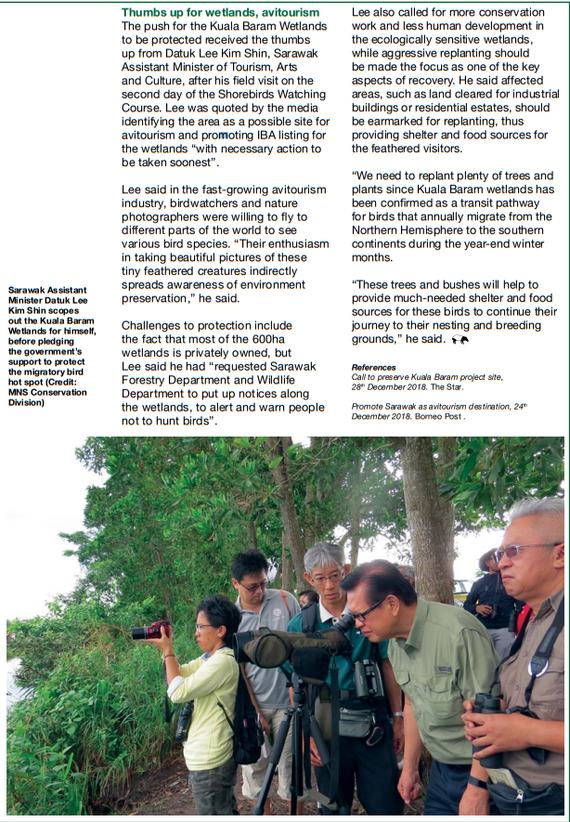

Down south in Johor, Branch Chair Abbott Chong related that river and shoreline pollution continued to plague the state, leading to dire issues such as pump shutdowns, low fisheries yield and dwindling numbers of birds on related shores, one such being Danga Bay. Actions taken by the Branch included awareness activities, engagement with the public and schools, workshops and working visits, participation as technical advisors in the Raja Zarith Sofiah Wildlife Defenders Challenge themed “Johor’s Mighty Rivers”, beach clean-ups, mangrove rehabilitation activities and tree planting.

There were also highs and lows at the Panti Bird Sanctuary, one of the top birdwatching sites in Southeast Asia, Chong said. The troughs were the diminishing bird count, which was attributed to loss of forest connectivity, heavy trucks plying the area, and army training. He added that the sanctuary was officially opened a decade ago with a multi-million-ringgit complex meant for conservation and education, but this facility remained unusable due to lack of water and electricity supply.

Chong said the Branch had been pushing the authorities without much success until recently. “We secured the cooperation of the Forestry Department and sought help from Nature Society Singapore to start a scientific expedition,” which kicked off in March 2019 with more than 100 volunteers and the utilisation of camera traps. The positives have included fewer reports of poachers, illegal campers, heavy trucks and army exercises, he said, leading the Branch to be optimistic about the future of Panti.

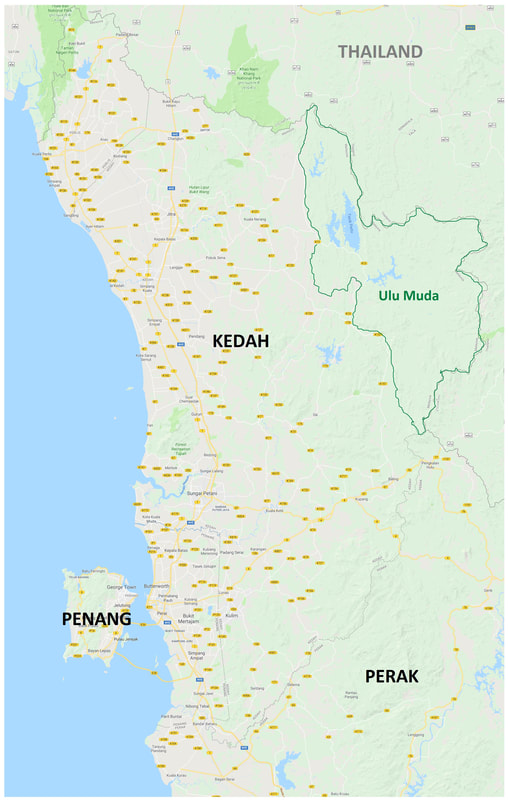

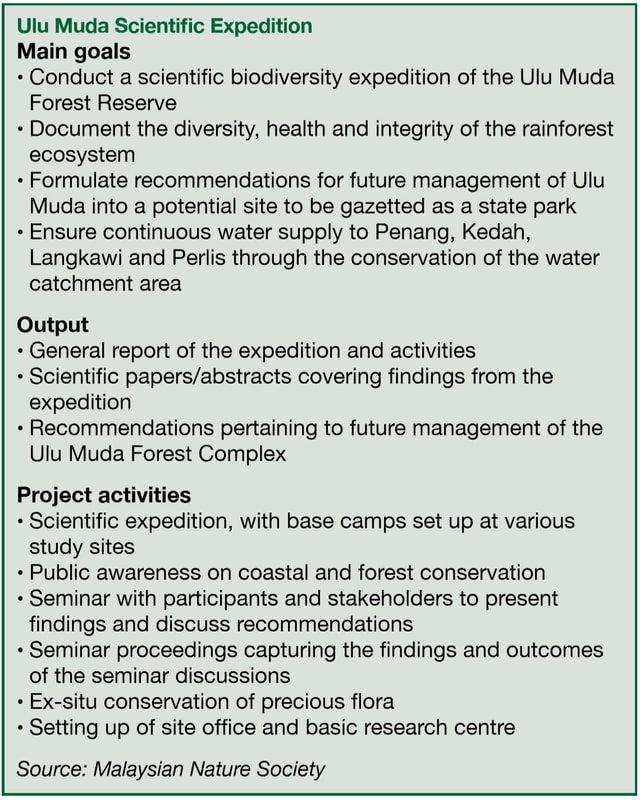

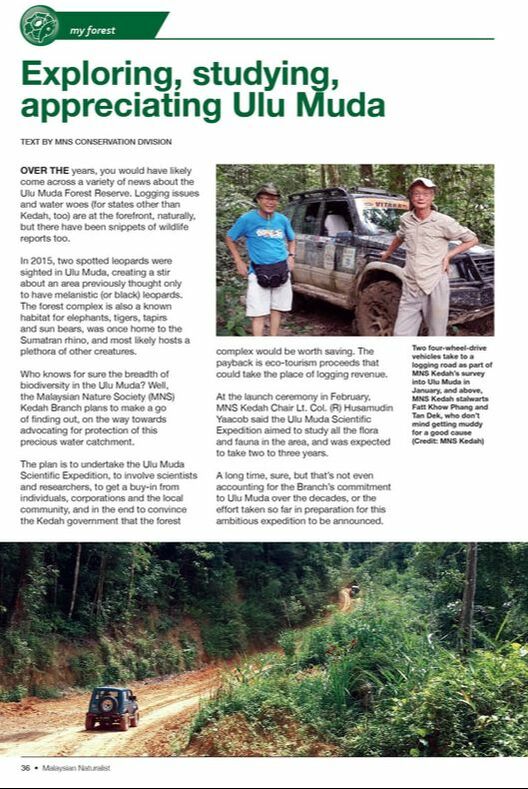

Up north, the audience heard about MNS Kedah Branch’s efforts to save the Ulu Muda Forest Reserve, which is threatened by logging, with Branch Secretary Phang Fatt Khow outlining the importance of scientific expeditions in pushing for the protection of forests.

“The strength of MNS is that when we propose a place to be conserved, we back it up with scientific data,” he said, citing the success of Endau-Rompin and Royal Belum as inspiration to save 160,000 hectares of forests that provide water to the states of Kedah, Perlis and Penang, irrigate the rice bowl of Malaysia, and ensure industries prosper.

Then there is the question of biodiversity. Phang said preliminary surveys had recorded 111 species of mammals, 305 birds, 63 reptiles, 50 amphibians and 33 freshwater fishes, while they had only scratched the surface with regard to the riches of the area’s flora, especially new species or those with pharmaceutical properties.

The presentation also detailed the steps taken so far to make the Ulu Muda Scientific Expedition a reality, especially the highs when it gained attention from state entities and also the Menteri Besar, and plans to urge the Kedah government to gazette Ulu Muda forests as a State Park.

In the final presentation for Tapir Talks 2.0, MNS Kuching Branch reported on the Rapid Assessments of the Helmeted Hornbill in Sarawak, which were carried out in July and August 2019. The objectives were to identify key helmeted hornbill sites, assess their feasibility for long-term conservation, identify current and potential threats to the species and other biodiversity, and conduct interviews on local community knowledge of the distribution, local use, hunting and cultural beliefs regarding the helmeted hornbill.

Presented by Youth Member Ng Jia Jie, the Branch outlined the methodology and survey areas of the assessment, as well as the findings, which included photographic evidence of birds in certain areas and notation about bird sounds in other spots.

It concluded that despite data still lacking about the helmeted hornbill population in Sarawak, the assessment had confirmed the presence/absence of this critically endangered bird in the sampling sites, while the local community survey was beneficial in understanding threats to the species. The report called for the sites to be revisited, and sampling conducted on a longer duration and by surveyors with respective expertise.